Considerable efforts have been made in Europe to reconcile different countries through a unique process of publicizing and harmonizing differing readings of past conflicts. A utopian vision has come into being with the aim of homogenizing divergent historical narratives. However, these attempts at harmonization have run up against national political realities. Issues of identity and the desire for recognition—features common to all European countries, as they tend first and foremost to promote their own national histories—remain key impediments.

The case of relations between Poland and Ukraine is particularly noteworthy in this respect because it is fueled by both top-down state initiatives and bottom-up citizen initiatives.

After the fall of communism, the new Polish elites’ vision of post-communist geopolitics moved them to reduce the potential for conflicts around memory with Ukraine and to achieve reconciliation. Since 1989, the issue of Poland’s attitude toward Ukraine has been a Polish foreign policy priority. Polish public policy toward Ukraine was therefore characterized by the dichotomy between choosing a memory policy and the weight imposed by memory of painful wrongs undergone in the past.

This same dichotomy may be seen in all initiatives taken by representatives of civil society.

Conflictual references concerning the extremely distant past and the key figures implicated in historical controversies have little weight or influence on today’s memory issues. This applies to Bohdan Khmielnitskyi (a Cosack military chief, 1595 to 1657), whom the Ukrainians consider a hero in the battle for independence from Poland.

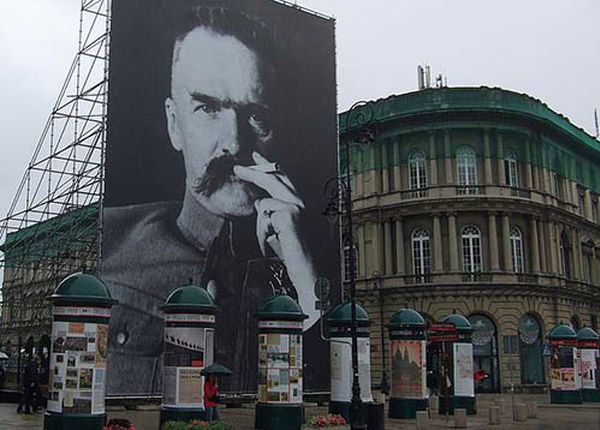

Other Ukrainian and Polish historical figures (Stephan Bandera, Symon Petliura, Jozef Piłsudski) have greater weight when it comes to assessing respective Ukrainian and Polish wrongs. These figures continue to haunt political issues around memory, influencing the forces that are hostile to reconciliation. They pertain to much more recent history (1918-1947).

Two facts had crystallized passions and worked to spark conflict. Namely: the massacres that took place in Volhynia and eastern Galicia in 1943, perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists against rural Polish populations, and an action known as the “Vistula operation” devised by the communist political police in 1947 aiming to ethnically cleanse Poland’s eastern territories.

In 1991-1993 the historical journal KARTA, linked to the Solidarność union movement, received much correspondence on the subject of the “

massacres,” including repeated demands to have those “crimes” described in detail, enabling people to speak openly at last. In many cases this was a reaction on the part of victims and victim associations against the conciliatory doctrine recommended by another journal, Kultura.

In the face of such strong indignation and manifestations of hatred, the KARTA center decided to organize a meeting between Polish and Ukrainian historians to deal with the issue. The name found for the discussion topic was as neutral as possible: “Poles and Ukrainians 1918-1948: difficult questions.”

Despite many divergences, the 11 Polish and 11 Ukrainian historians agreed on a text presenting the state of the art of mutually accepted knowledge on a set of conflicts that occurred in the first half of the twentieth century. All participants were able to co-sign a single text. They left the meeting feeling quite optimistic, thinking they would now be able to debate which side was responsible for doing what.

At this point two other actors of civil society entered the debate: the International Association of AK Soldiers (Polish Home Army, Volhynia region), which participated in the first historians’ meeting and wished to pursue the dialogue, and the Ukrainians of Poland Union, which got involved somewhat later.

The effort made on the initiative of civil society groups left its mark: 10 volumes of debates were published in Polish and Ukrainian. However, as the figure of the victim became more detailed over the course of the debates —making the responsibilities for the victim’s suffering more clearly—the goal of reconciliation became more difficult to attain.

What remains of this process today?

The impact of the historians’ commission was very slight. As one participant confided, the aim was not so much to reach a wide audience (the media accomplished this) as to “prove—not so much to the society at large as to a certain elite—that it was possible to debate together the themes of the past dividing the two nations … . Politicians had in a way been ‘relieved’ of handling … historical issues and risking conflict because civil society and historians’ organizations assumed the weight of these debates” (A. Paczkowski).

Nonetheless, President Victor Yushchenko, a friend of Poland, arranged for the Ukrainian Stepan Bandera to join Ukraine’s Pantheon of National Heroes, much to the disapproval of Poland, for whom Bandera was first and foremost a Nazi accomplice responsible for the ethnic cleansing campaigns. This sufficed to sow the seeds of distrust and significantly undermine the reconciliation process.

More recently, a positive direction has been indicated by the churches, in the form of a joint call from the Polish Catholic church and the Ukrainian Uniate and Orthodox churches, declaring: “We wish to pay tribute to the innocent victims, but also to ask God’s forgiveness for the crimes committed, and to call on everyone, Ukrainians and Poles alike, to courageously open their minds and hearts in the interests of achieving pardon and reconciliation”