Turning and turning in the widening gyre;

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world (…)

The Second Coming, W.B. Yeats

“The centre cannot hold.” This expression rattled around my head on the bus between Wrocław and Łódź. William Butler Yeats wrote these words when the First World War had ended, and as the Irish War of Independence began to unfold, capturing the sense of a moment in history when all was falling apart and “surely some revelation is at hand”. Queue 2020.

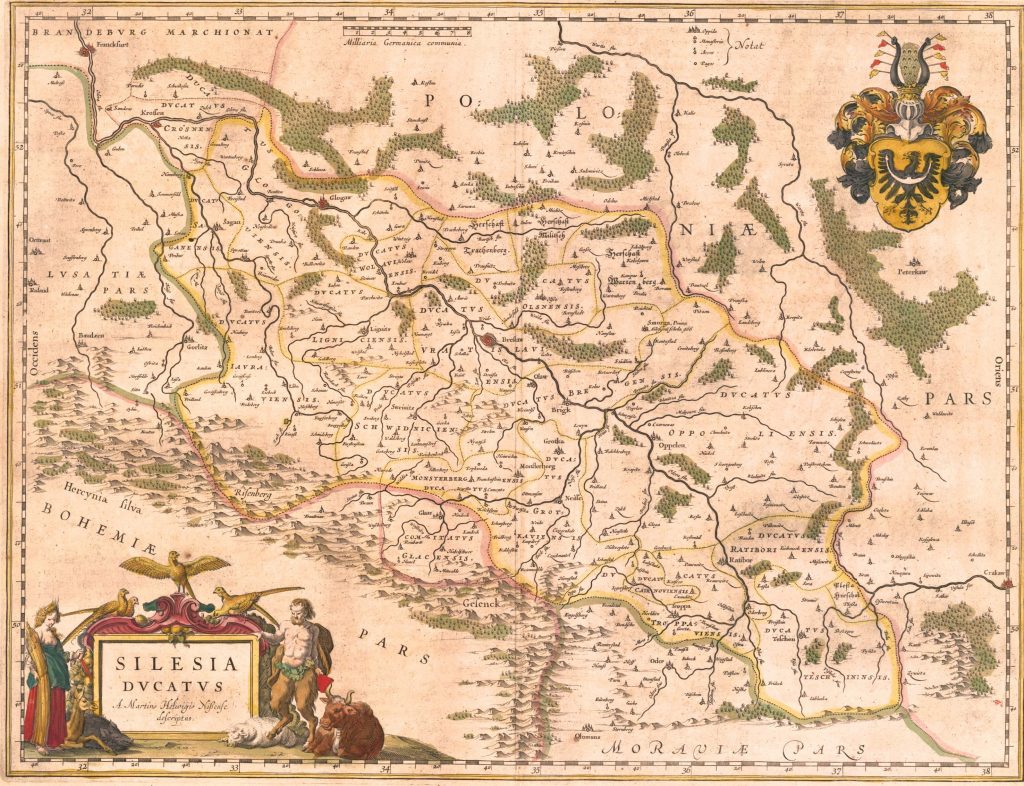

At a time when identity is being re-examined as something more fluid, and the sovereign state is being redefined as something vaguer, where borders are being questioned, and an international epidemic has shaken or even broken our concepts of governance and stability; our world has rarely seemed so uncertain and fluid. That the centre cannot hold. This was the backdrop of the Natolin study trips which took place last fall; for me it involved a trip to Poland’s Silesia region.

Silesia, a place with its own culture and language. Throughout its history it was in flux and under new management, even to this day divided between three nations, and is no stranger to change and uncertainty. And yet, even this region is left reeling by the quickening stream of events. For the first time since the Czech Republic and Poland joined the Schengen area, this summer the borders closed between the two countries, dividing the Silesian community that is spread beyond both sides of the border. It was an unwelcome reminder of darker days.

Silesians see themselves as having a distinct identity. This identity exists alongside their Polish or Czech or German one, and, now, with their European one. In the past, the Hapsburgs would have demanded loyalty to the Austrian empire or Catherine the Great loyalty to the Russian Empire, a local identity was then left to exist even if subsumed to an empire. Now, such hierarchical thinking would be seen as uncouth. Identity is recognised as far too ambiguous and mysterious a thing to slap a number onto and rank. A Silesian identity, for example, can run alongside the Polish one, and alongside the European one – interweaving and swooping in and around others. This, perhaps, shows a success of the EU, or a growing maturity among Europeans. By granting a secondary citizenship, a European citizenship, one which neither subsumes or cancels or is hierarchal to any national identity, the EU opened a door to a more ambiguous and forgiving concept of citizenship (and citizenship is de facto a matter of identity). This is a concept of identity centred not around us and them, or what you can and cannot be – a black and white picture – but an identity as a facet of a multifaceted object; and so a previously two-dimensional concept was made a three-dimensional one.

The “chicken and the egg” debate – of what came first: EU and its citizenship, or a pan-European identity – has been rumbling for some time, especially in Northern Ireland, another hotbed of identity discussions. Either way, the result is clear and could be seen in our study trip. National identity has undergone a transformation in the last half century. This struck me during a conference with cultural Germans who live in Silesia and who campaigned throughout the later-half of the 20th century for their cultural rights to be expressed, which had been previously oppressed by the communist authorities. Cultural Germans, in Silesia, in Poland, in Europe; multiple identities not nested into each other and stationary, but alongside each other, running, weaving, at times stronger than other times. Yet, that does not mean that Silesia is a multi-ethnic paradise. The German minority spoke of racist attacks, the most evidentiary example being road signs erected in both Polish and German routinely vandalised; with the German being erased.

While minorities may have found a way to reconcile the different facets of their identities, that does not mean the majorities have. Repeatedly and consistently, elected representatives or the civil society representatives we met were questioned on Poland’s failures to protect yet another minority (another identity) that was forbidden from exercising its right to express itself: this is the LGBTQ community. Some agreed that the suppression was shameful while others dodged the issue. But this topic is not going anywhere. Now and again, in apartment windows, in every city in Poland, if you look closely, you can see the rainbow flag. And a cohort of young students travelling to Silesia continued to keep the issue on the table.

The irony is that people who live and work in these borderlands such as Silesia, where cultures and identities are more ambiguous, less certain, and more mysterious and fluid, seem to know themselves better than those peoples in the “centre”. I would argue that the centre can be a state of mind as much as a physical space. The centre can be the heartland physically, but also the mentality of majorities that their culture is the “centre” of the nation – the ideological heartland. To them, other cultures and ways of life are the periphery, the “borderlands”. Peoples of the centre have a more fixed and unitary sense of identity, are more sure of their place, for better or worse. Yet, ironically they are also often the people who show signs of more insecurity, of more fear, of more uncertainty, with less tolerance and time for the different. The centre is by its nature self-centred; it has to be, to create the gravity needed to hold the nation together. It often does not look outward, but in. It does not concern itself enough with the edges of itself, where it meets the outside world and its nature mingles and blurs with something else, and creates something new and exciting. Perhaps, the centre attempts to hold too much.

This is not to say the borderlands are paragons of toleration and wise men of the winds of change. The paradox of the borderlands is that while you can find the mingling of cultures and races like nowhere else, the most fervent entrenchment of identity politics and narrowmindedness also exist there. Sometimes when surrounded by the “other”, fear and subsequently a siege mentality can set in. This is illustrated by the Texas border area and Mexico; or, yet again, Northern Ireland. It is not the people from the centre who drive down to vandalise the German minorities signs in Silesia. In this regard the borderlands, examples of culture and identity as something living and evolving, can also be the very worst examples of the concept of identity as something static and entrenched, and to be defended at all costs. They can be where the “centre” as a mental construct truly is at its strongest, and most dangerous.

Silesia seems to have avoided the worst attempts to build a wall, whether a physical or mental one, around identity and culture like other borderlands. Yet some still remain. At one point, I witnessed a member of the LGBTQ community question a member of the Germany speaking minority what they have done to defend the rights of another minority, and whether they had defended the rights of the LGBTQ community. The question was clumsily dodged. Yet, the exchange, as disappointing as it was, was also an example of the evolution by attrition; the exchange of ideas and debate. Such moments are where the centre begins to be eroded and something new, possibly, can begin.

Perhaps, it has to do with the people of Silesia having had to reconcile a long time ago with the nebulous waves of time that break apart empires and recede; leaving behind new states, and bring new peoples, new ideas. The same way fishing villages learned never to presume they knew the sea, the people of Silesia learned not to presume they knew time; not to presume anything is constant, or certain. They have always known that the centre is only fleeting. The gyre was always moving and widening, the falcon would always fly away, the centre never had a chance of holding, everything is constantly evolving.

Great Silesian cities soared up in plumes of industrial smoke and sweat during the industrial revolution, powered by the mines being furiously dug beneath to excrete coal for insatiable factories above. At the time it must have seemed this way of life was the new norm, and would stay forever. The factories appearing so solid, the might of incredible, clunking new inventions shocking the citizens into thinking a new permanent world order had very firmly established itself. But that world order had passed on as well. In the mines where once hundreds were employed and whole communities lived off the black gold of coal, we were taught about the transition from black coal and oil to green energies. The irony was not lost on anyone. The old mining areas of Silesia will need huge investments to cope with the change. The gyre keeps on turning, widening. Tomorrow, there’ll be another rotation, another revolution. In the words of Terry Pratchett, that’s the thing about revolutions: “they always come around again. That’s why they’re called revolutions.”

At the College of Eastern Europe, the former mayor of Wrocław, Rafał Dutkiewicz, spoke about the tension in Poland and how it is not about the EU, but about a rapidly changing world. New technologies and new concepts coming at a speed that is striking anxiety into the hearts of the rural citizens more than anyone. There is a fear of this sweeping change, and a fear that their identities, and the life they know, will be left behind to flounder in the quickening stream. They are afraid their centre is no longer holding.

Yet, maybe the centre should not hold. Actually, maybe it never did hold. We cast our minds back to the times we believed it did, when life was sure and certain, yet any Silesian would tell you that there was no such thing. A Silesian would, perhaps, tell you that Yeats was wrong. This is no second coming, it is about the hundred thousandth. In these times, when the gyre is turning faster and faster, those in the centre would do well to listen to them, to embrace ambiguity and change, rather than fanaticism and stagnation. This is not to say the anxieties of those afraid they will be left behind in this evolving world are not valid, but the solution is not for a region and a people to cower from change and cling to an old world, the old centre, but to assist everyone to move confidently forward with that change. The Silesians understand this. I began this essay with Yeats, but I might end it with another poet: Billy Joel.

We didn’t start the fire

It was always burning

Since the world’s been turning

We didn’t start the fire

But when we are gone

Will it still burn on, and on, and on, and on

This essay received the honourable mention commendation in the recent writing competition titled “Dispatches from the Borderlands” organised for students of the College of Europe in Natolin.