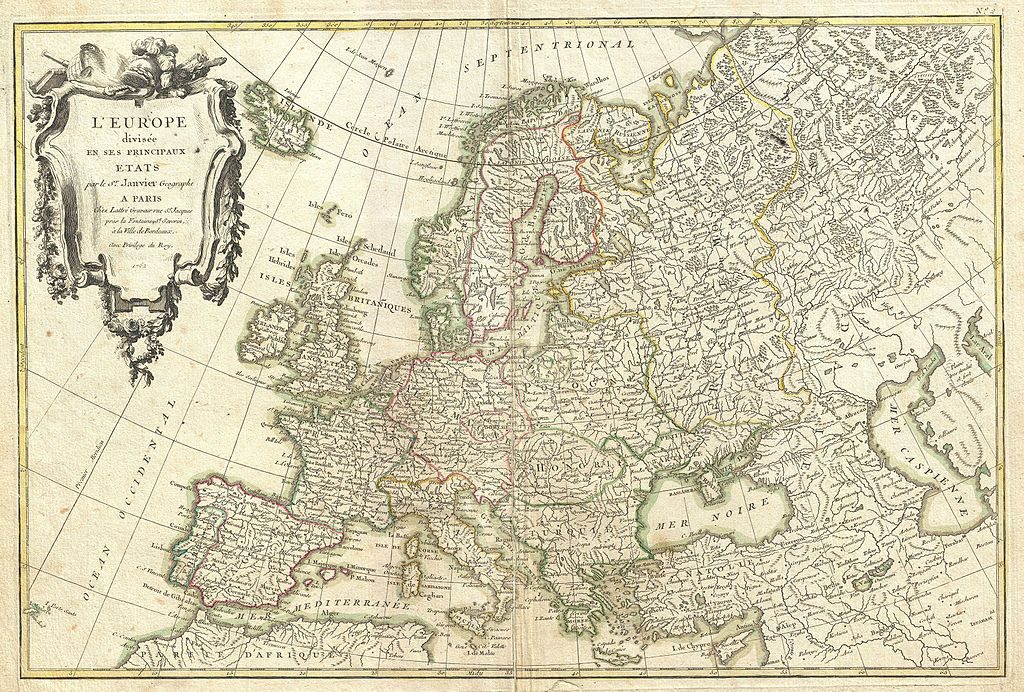

European identity is not based on external borders, which have been changing throughout history. But if boundaries are not a strong basis for understanding identities, then what is Europe? And what is “European identity”?

Before discussing European identity, we first need to have a common definition of Europe itself, which will serve as the basis of European identity. If we take the traditional geographical boundaries that are thought of as Europe, then entire groups of populations are left out. They include citizens of the European Union (EU) who live on islands that are part of France or other EU member states, which lie outside of mainland EU. Or many Algerians and other non-EU citizens who fought for freedom during the two World Wars. They serve the common vision and aspirations of the EU through military and other endeavours in the EU or in their home countries. And they send their children or grandparents to live and study in Europe.

From Argonauts to European Brotherhood

“Europeans” or “Proto-Europeans” often tried to stretch their geographical boundaries. Greek legends would claim that many nations originated from them. Armenians, for example, originated from an “Argonaut” by the name Armenos; Armenos of Thessaly. Such legends, according to some theories, aimed to legitimise the colonisation of other nations and justify the fact that they should all be centred around the “originator”. They would form a common wide identity that would stretch over continents. And this phenomenon is seen throughout world cultures.

Throughout the 20th century, it is easy to see that European identity, however defined, is very flexible in terms of geography and borders, just like it was in the past with Greeks, Romans or colonial European empires. Each time the EU embraces new member states, there is no global “identity crisis” for most EU citizens and for most of those who join the EU. Even Victor Hugo, in his beautiful opening speech for the World Peace Congress in 1849, envisioned Russia as part of the “European brotherhood” of countries (Hugo, 1849).

Geography and frontiers (including mental ones) are not as fixed and unmovable as they seem to be now. Both in terms of ideologies and in terms of world history, especially the history of the last four centuries, it is clear that external boundaries are not strong pillars and precursors in terms of defining and maintaining identities. This leads us to another question, namely…

If not Boundaries, Then What?

Any identity is based on memories and learned data. “I am a singer,” for instance, means that the given person has been singing for a while; they know how to sing, they learned it in the past, and have been singing (and/or desire to sing for a while in the future). Memory/past and aspiration/future are therefore two important components of any given identity. Members of a given society often see their collective identity through the prism of stereotypes. This manifests itself when they vote to join a transnational organisation or, on the contrary, close their borders to their neighbours. Their national identity is shaped by memories or perceived memories, just as individual identities are governed by specific traumatic or bright memories and perspectives. As Gellner puts it, “Cultures are sometimes invisible to their bearers, who look through them like the air they breathe…” (Gellner 1997, 94)

Behaviour (policies in case of the EU) is directly linked to favoured memories and the identity which rests upon those memories and aspirations. Behaviour is controlled to some extent by identity both on individual and communal levels. For instance, an anarchist will decide not to visit particular stores or not to use the services of particular organisations, labelling them as “capitalist”. Similarly, citizens thinking of themselves as Democrats or Republicans will largely defend and vote for the respective politician representing their party. Their choice is often based solely on the politician’s belonging to the same party. For the EU, this means that the given pool of memories and aspirations, and the qualities that describe the identity, will be defining its policies and behaviour internally and externally.

Intellect and bias

Intellect is usually controlled by a given identity, too. For example, a strong Christian identity will dictate the individual’s thoughts and arguments, favouring a specific thread of biased thinking. The stance on abortions or gay marriage and the arguments to support and justify that stance will be cherry-picked from specific sources (a vision of a world that abides by the rules of the Bible, in this example). The term “biased” applies to any identity (Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, atheist, democrat, capitalist, anarchist, socialist, cosmopolitan, European, and so on). Any sort of conservative, liberal or any other type of thought, policy, and vision is based on perceived identities.

Any good and bad policy and action can be justified on the basis of any identity. The “bourgeoisie” was, for instance, hunted down and exterminated in France at the end of the 18th century in the name of enlightenment and secularism. The whole policy of Robespierre’s politics of “terror” (a word the revolutionaries themselves used to describe their politics) was to serve the high purpose of freedom, secularism and enlightenment. Similarly, the undertakers of the Chinese “Cultural Revolution” burnt temples and books, and persecuted and executed various social groups. Individuals and societies are both good at justifying anything they want through arguments, but there is more to that process of favouring specific arguments than pure intellectual reasoning.

European Identity in the Past

It is possible to draw the conclusion that specific memories should be carefully and consciously selected or favoured over others to avoid processes and policies that lead to victimisation, segregation, bloodshed, revolutions, and other negative phenomena. It took two World Wars to reject the win-lose paradigm which would require Europe to split along with lines of winners and losers and which would breed the victim mentality and the desire to avenge.

How do we favour some memories over others? Do you remember what you ate at breakfast on 25th November 1995? And what about your birthday or the day you got married? Both are memories. One is “lost” to the conscious mind, and the other is underlined as “important”. This process is the same on the collective, national, international and other levels, too. Nobody cares about May 10, for instance, in the context of EU. But May 9 is celebrated as Europe Day. This is a clear example of selective memories, just as in the case of individuals.

The two World Wars brought so much destruction that they still determine how we form memories in the present day. For the purpose of establishing what the European identity is, it is important to ask whether the Second World War was the beginning of Europe’s unification or if it was the culmination and the end of a country-state mentality for the EU member states The Union was established for the purpose of cooperation between several states and societies after the war ended. Trying to overcome a country-state mentality would seem like a contradiction of the principles of the Union.

There is, however, a huge difference between establishing a static state of peace and creating a Union through a dynamic state of cooperation. If war is to be taken as an important memory for the history and identity of modern EU, then peace is to be seen as the highest striving for the EU member states, as it is set in the Lisbon Treaty. But should peace really be the highest aspiration?

Peace vs Cooperation

Peace, the warring states concluded, was not enough after two World Wars. Peace is a static state of being. However, France, Germany, Italy and other state leaders realised they needed more than a static state of peace: they needed dynamic cooperation and interdependence, a broader sense of co-dependence, and unity in motion. Or else, peace could fail again, just like it did after the First World War and other European wars before, especially with the win-lose paradigm, where there is one side which wins and another which loses and wants revenge and victory, not peace. Merely craving for peace might revive the win-lose paradigm, as some states (e.g. modern Russia) can be perceived as a threat to peace. If peace is to be maintained, then measures should be taken against those who threaten that peace, on the level of this paradigm. Therefore, a mere striving for peace is not only insufficient for modern-day Europe and world, but it may even serve as basis for a narrow-minded perception of Europe and its purpose.

Moreover, if the purpose of the EU is to ensure peace for its member states, then why is it accepting new members? Why is it expanding? Peace is a static state of being, an equilibrium to be kept, and for it to be maintained, a fair amount of motionlessness and inertia is required. New member states, cooperation with the neighbours, enlargement, all these activities may shift that equilibrium (which may be imaginary on many levels) and cause new crises and a need to readjust, innovate, come up with new mindsets and policy and relationship tactics. This is a place where the classical notion of peace seems obsolete and even dangerous if left alone.

Conclusion

“To live a good life, it’s not enough to remove what is wrong with it”, states the founder of Positive Psychology, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Chang, 2006, 337). It is not enough to end wars, eradicate poverty, and fight against the negative phenomena. Therefore, peace itself is simply not enough, neither on individual, nor on supranational levels.

As of today, “I am a European” is a phrase uttered in dozens of languages. The European identity has a long history of its own, and just like in the past, this identity undergoes change and expansion. Identities wear away as clothes do. More adaptability, openness and willingness to embrace and expand will mean a longer lifespan for Europe and for the European Union, its more concrete manifestation.

Bibliography and further reading:

Council of Europe, Winston Churchill, speech delivered at the University of Zurich, 19 September 1946 available at https://rm.coe.int/16806981f3

Chang Larry, ed. Wisdom for the soul: Five millennia of prescriptions for spiritual healing. Gnosophia Publishers, 2006, 824 p.

Cram, Laura. “Identity and European integration: diversity as a source of integration.” Nations and Nationalism 15, no. 1 ,2009, pp.109-128.

Discours d’Ouverture au Congrès de la Paix à Paris, 1849, Victor Hugo, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Kkrr8pH26U

European Identity: Concepts of Identity – Laura Cram, https://youtu.be/nnTFxOHZafs

Gellner, Ernest. “Nationalism.” , New York Press, New York, 1997, 114p.

Herman Van Rompuy, President of the European Council (Extracts from the Nobel lecture 2012), https://youtu.be/Y4hyyqoOuY0

Klein Lars. “How (Not) to Fix European Identity?.” Europe–Space for Transcultural Existence?, 2013, 57p.

Lisbon Treaty, http://www.lisbon-treaty.org/wcm/

Stråth Bo. “A European identity: To the historical limits of a concept.” European Journal of Social Theory Vol. 5, No. 4, 2002, pp.387-401.

Victor Hugo au Congrès De La Paix De 1849, available at https://www.taurillon.org/Victor-Hugo-au-Congres-de-la-Paix-de-1849-son-discours,02448

Wendt Alexander. “Collective identity formation and the international state.” American political science review, Vol. 88, No. 2, 1994, pp. 384-396.