On June 7, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, published the Joint Communication on Resilience[1]. The Communication, entitled “A Strategic Approach to Resilience in the EU’s External Action”, clarifies the concept of resilience that was introduced in the Global Strategy of the European Union[2] published last June 2016.

In the Global Strategy one of the objectives of the Union is to strengthen the resilience of states and societies, defining resilience as “the ability of states and societies to reform, thus withstanding and recovering from internal and external crises”. This resilience, however, is not only directed at the countries of the European Neighbourhood, but also within the EU itself.

A concept that goes beyond the divisions between policy areas

The concept of resilience appears more than 40 times in the Global Strategy. For this reason, it has attracted the attention of scholars, who are still arguing over a clear and unambiguous definition. In fact resilience, a concept that derives from biological sciences and has recently been employed in psychology, is “a means not an end”. The High Representative’s recent communication therefore intends to clarify the use of this term when applied to the Union’s foreign policy.

Indeed, resilience is a term that needs to be contextualized when used. In the recent document resilience adopts several facets, which demonstrate how this concept is transversal to the some policies of the Union. The concept is first applied to the Union’s foreign policy with the emphasis on strengthening the resilience of partner countries and their institutions and societies and their economies. This means helping partner countries to be able to respond to crises autonomously, whether they are political, social or economic. For example, promoting the resilience of Mediterranean countries could be translated in helping to identify tools that make them capable of responding to a crisis they might face in the future, such as the high youth unemployment which, as in the past, caused turmoil in the Region.

However, resilience is not just about crisis prevention. Indeed, resilience aims to act on structures to respond to crises in a way that tries to go to the root of the problem, and not responding with an emergency approach. For example, in terms of long-term security, humanitarian and development crises, resilience is geared to responding to the structural fragility of the countries in trouble, making them able to cope with a crisis by fostering the development of their resources, diminishing in the meantime also their dependence on external actors.

Resilience is also crucial in conflict prevention and, therefore, in the area of security and defence policies: promoting the reform of the security sectors of partner countries strengthens them in maintaining a stability that works not only for the country itself, but even for Union’s security. Moreover, the concept of resilience implies that this is done in compliance with human rights standards, allowing the Union’s external action to be attached to respect for human rights through “principled pragmatism”.

From promoting democracy to enhancing resilience?

Several authors have considered this change in the Union’s foreign policy as a renunciation of a European values-based approach in its external action. In fact, this approach seeks to meet the needs of partner countries. It is surely, as noted by Mai’a K. Davis Cross, “a realistic assessment of what is possible”[3].

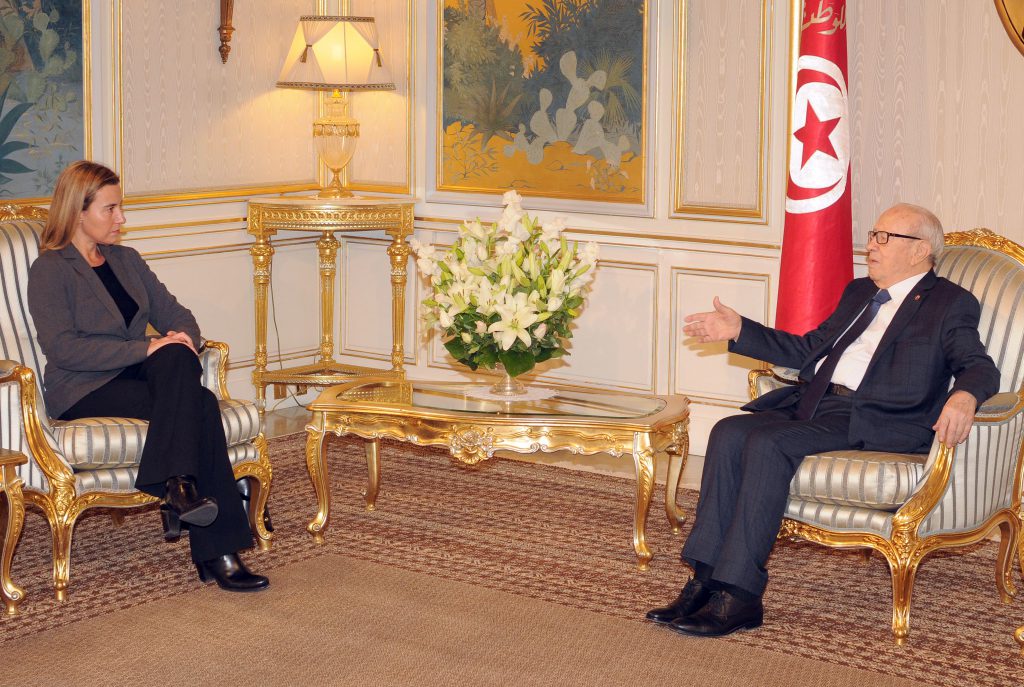

EU’s democracy promotion policies in the context of the Neighbourhood have in fact been quite unsuccessful, if the case of Tunisia is excluded – here by contrast internal factors have contributed to stabilization and the democratic transition. In addition, the concept of “promoting democracy” is certainly not perceived with favour in the MENA region, where this purpose has been used to justify armed conflicts, such as the last war in Iraq.

The promotion of democracy in this region has mostly failed because of the lack of correspondence between the demands of the populations and European proposals. In unstable countries, where an individual can struggle to have access to primary goods – because of their prices for example- or where is likely to remain victim of violence as part of daily life, the promotion of democracy is certainly not the priority.

This does not mean that it does not have to be considered anymore in the future, or that we must ignore respect for human rights: resilience seeks to respond to the challenges of our neighbouring societies by addressing the resolution of their structural problems, and does so in a way that promotes, fundamentally, respect for human rights, so as to encourage the emergence of democratic societies upon request of the citizens of these countries, so that the new system of values is more legitimated than when democracy is promoted from the outside.

Luigi Cino is a Ph.D. Candidate at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa and College of Europe in Natolin Alumnus (Chopin Promotion, 2015 – 16)

[1] European External Action Service, A Strategic Approach to Resilience in the EU’s External Action, available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/27711/joint-communication-european-parliament-and-council-strategic-approach-resilience-eus-external_en

[2] European Commission, EU Global Strategy, available at : https://europa.eu/globalstrategy/en/global-strategy-foreign-and-security-policy-european-union

[3] Mai’a K. Davis Cross (2016) The EU Global Strategy and diplomacy, in: Contemporary Security Policy, 37:3, 402-413. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13523260.2016.1237820